For many of us who are descendants of Cape Verdean immigrants who arrived in the United States prior to Independence in 1975, the subject of Cape Verdean Independence and Amilcar Cabral, the father of Cape Verdean Independence, is often learned later in life. For many reasons, identification and connection with a liberation movement in Africa has often been quite elusive. Knowledge of and pride in our European ancestry often overshadowed even acknowledgement of our African ancestry.

From my own reading of his speeches and by most other accounts, Amilcar Cabral was a brilliant theorist and strategist. Understanding that the history that resulted in the creation of the “Caboverdeano” was intrinsically woven with the people of mainland Africa, he sought to integrate Cape Verdeans into the struggle for liberation on the mainland to rid Guinea Bissau AND Cabo Verde of colonial rule. The unification of Cabo Verde with its African brothers was a major priority. But in the years during the struggle and even today, it is not hard to find elements of resistance to the ideas of Cabral and even the idea of Cape Verdean Independence, itself, within the Cape Verdean community in the United States and the Diaspora.

My question has always been WHY???

Mr Salah Matteos, Cape Verdean- American from New Bedford, gives one of the most insightful explanations I have come across in the following excerpt from Ufahamu, Volume III, Number 3, Winter 1973 pigs 43-48 in special issue “In Memoriam Amilcar Cabral, 1925-1973 (1)

The Cape Verdeans and the PAIGC Struggle For National Liberation

An Interview with Salahudin Omowale Matteos

[As many of our contributors to this issue point out, one of the problems which the PAIGC has had to face, but one which it has handled with a great deal of tact and imagination, has been the problem of integrating the Cape Verdeans into the struggle for national liberation. Because the Portuguese used the islands as a major staging post in the infamous traffic in slaves, many Cape Verdeans have had to undergo varying degrees of cultural disorientation and alienation, some of them, alas, suffering an outright loss of identity (2)

During Cabral’s last visit to the United States, it was decided that there was need for a PAIGC Support Committee in the U.S. part of whose assignment would be to raise the general level of awareness among the Cape Verdeans in this country. As Gil Fernandez said, “Most American Cape Verdeans are either ignorant of or apathetic towards the fighting going on in the homeland for the past decade.” One of those intimately involved with the founding of the Support Committee was Salahudin Matteos.

Matteos was born in New Bedford of Cape Verdean parents. After more than a decade of involvement with civil rights, black liberation and peace movements in this country, he left on a trip to Africa and was able to meet with other Cape Verdeans not only in Guine but also in Gambia and Senegal.

Since his return, and on a mandate from the Committee, Matteos has been touring several U.S. colleges and universities, explaining the goals of the PAIGC and soliciting the support of civilized humanity. It was on the invitation of Ufahamu that, on February 23, 1973, he gave a talk to a large group of students at the African Studies Center at UCLA.

We are pleased to carry a transcript of that presentation. We also urge our readers to make whatever contribution they can to the PAIGC Support Committee – Three Pyramids, Box 1510, Duxbury, Massachusetts. Ed. Note.]

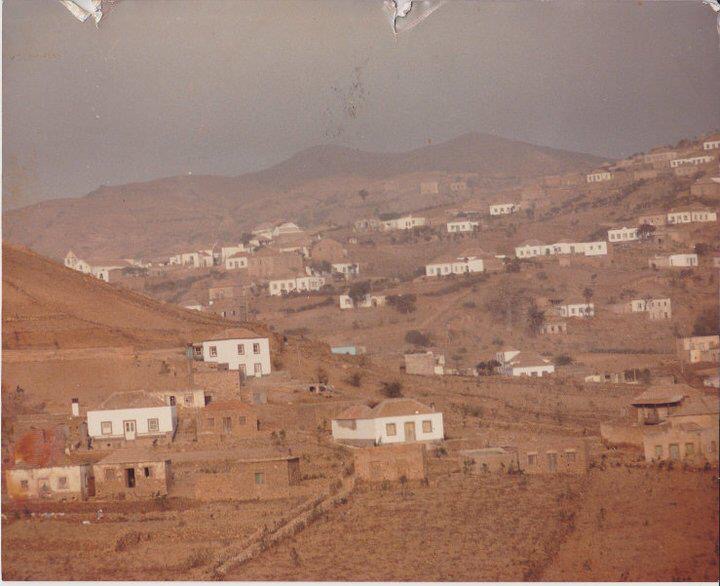

I think it would be very useful to begin by giving you a little background about Cape Verdeans. Not too many people know about Cape Verdeans, but that is easily understood. The people who live on the Cape Verde islands were people who were enslaved by the Portuguese and taken from Africa beginning in the fifteenth century. The Portuguese were the first Europeans into Africa and they led the way for other Europeans. One of their first stops was around Senegal, but as they were not successful in establishing fruitful contact with Africans, they went further down the coast to Guinea Bissau. (Its proper name in Africa is Bissau). The Portuguese enslaved the Africans of that area concentrating on societies such as the Fulani, Balanta, and Mandingoes. These Africans were taken to the Archipelago of Cape Verde off the coast of Africa. These islands are some two hundred miles due west from the lower part of Senegal; the farthest point from Africa is about 450 miles. And, of course, Portugal is almost 300 miles away.

All the sorts of atrocities which go hand in hand with slavery were perpetrated by the Portuguese system. On different islands a variety of methods were used to deal with the African mind in order to reshape it. One phase of the enslavement of Africans was to send them to other parts of the world to work. The Portuguese called them oontractos. It was the Portuguese who originated the idea that Africans were not people, but animals. There is a word that we say in Creole, negro cachin (3) which means in Portuguese “blacks are not people.” This gave way to the wholesale slaughter and exploitation of Africans because this was the excuse for treating them in such an inhumane manner.

An example of the different methods used on Africans was that on one island the Portuguese brought together African men and Portuguese prostitutes, who bore children. The fathers were then killed while the women brought up the children to speak Portuguese. Today, most of us do not speak Portuguese except for a few educated in recent years. We speak our own language, Creole, which is part African and part Portuguese.

Cape Verdeans came to the United States only within the past century. In my case my grandparents came to this country seventy years ago. My grandparents were born on Cape Verde. You will find that they came here primarily as contractos. However, they did not view themselves as coming just as workers; they were also looking for freedom because they recognized that on the island they were continually being starved to death. Since the middle of the 18th century, more than 250,000 people have starved to death. More people have died of starvation than have ever lived on the islands. There are thousands of Cape Verdeans in the United States who were forced to leave the islands because of famine. Cape Verdeans have been forced to go to many other countries such as Senegal, Gambia, Holland, France and many other parts of Europe and Africa because of starvation.

Cape Verdeans were brought to the New England area as freed men although they were treated as indentured servants. Thus, a kind of false pride has developed among Cape Verdeans here who say that they are different from Afro-Americans because they were not brought to this country as slaves. But I would like to make a correction. There is no difference between Afro-Americans and Cape Verdeans. The only difference is that the Africans who were taken to Cape Verde were enslaved by the Portuguese and the Afro-Americans who were brought to this country were enslaved by other Europeans. We were both enslaved by Europeans to be used as cheap labor.

Cape Verdeans were brought to the New Bedford and Cape Cod areas, the tri-state area of Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts. (About 75,000 Cape Verdeans presently live there.) Their main source of employment was working in cranberry bogs for white landowners who were transforming this land for producing cranberries. It was the backs of my grandmother and grandfather who made Ocean Spray what it is today.

Because Cape Verdeans have a rich African heritage, you will find that we have a style of living which is very similar to that of Africa. The kind of foods that we eat are similar to African foods. We eat mandioc , oous-oous (4), arros, manchupo. Our mothers also used to wear long dresses and tie up their hair.

Unfortunately, Cape Verdeans in this country do not identify with our African heritage because they have been brainwashed over several centuries into relating to something which was false. For myself, it was through my contact with Amilcar Cabral and traveling through the liberated zones that I gradually became aware of who I am as an individual. This was a very traumatic experience. I was thinking that I was Portuguese, but I knew that I was not European. So I began to involve myself as a Negro. But the irony is that while I was trying to become a Negro, Negroes were trying to become Black!

Accordingly, it is one of the main purposes of the PAIGC Support Committee to organize and mobilize Cape Verdeans in this country to help support the liberation movement of the PAIGC. We are attempting to give Cape Verdeans the facts about the suffering and famine on Cape Verde islands and how best we can help to raise the level of consciousness of Cape Verdean people to the true facts of their enslavement by the Portuguese system of colonialism. We are hopeful that when Cape Verdeans see the contradictions of their history, they will relate to our Cape Verdean African heritage.

I would now like to give you an idea of the purpose and direction of the PAIGC. The PAIGC has been fighting against the Portuguese colonialists since 1963, but the Party was organized several years before that. We have been fighting a “hot war” since 1963 and have liberated more than two-thirds of that territory. The PAIGC goal is the total liberation of Guinea Bissau and Cape Verde islands. After ten years and more of fighting, the people of Guinea Bissau have established an administration and set up schools and hospitals which had never existed under the Portuguese. Last April, the leadership of the PAIGC invited the United Nations to send a special mission to visit the liberated areas and to find out in loco where the liberated areas are and “how they are administered.” After the visit to those areas, the mission recommended to the General Assembly that PAIGC should be considered the only legal authority in the colony. (5)

Under the Portuguese system, very few Africans had the opportunity to go to school. Amilcar Cabral was one of those few who was able to receive a university education; he was trained as an agronomist. Although he was born in Bafata, Guinea Bissau, Amilcar Cabral is a Cape Verdean of Cape Verdean parentage. He came from a privileged class of Africans. However, he was able to understand the magnitude of the problems of his people. He was a brilliant theoretician and pragmatist and recognized that Africans need not borrow ideas wholesale from all over the world because he believed that no one had a monopoly on knowledge.

As I have mentioned, the purpose of the PAIGC Support Committee is to organize and mobilize Cape Verdeans in the United States to help support our liberation movement, but we are also informing all African people in this country to become involved in supporting and relating to our struggle against Portuguese colonialism in Africa. The fight against Portuguese colonialism is the most important struggle in Africa today. The Portuguese are the last bulwark of European colonialism in Africa. They were the first to come and they are the last to leave. Most of the aid supporting Portugal comes from the United States through NATO to help Portugal maintain her wars of oppression in Africa. In Cape Verde, we are not yet fighting a “hot war,” but we do have a strong clandestine organization which is working effectively. That is significant for those of us who are involved in the liberation of our people.

I want to make it very clear that when I talk about Portugal, I am talking about the Portuguese system, not the Portuguese people. Our struggle is not against the Portuguese peasant or farmer who is suffering at the hands of fascism, but against the oppressive Portuguese system of colonialism. So, we even ask the Portuguese people of this country that they should be about the business of relating to what is happening in Portugal because they should realize that what is happening in Africa only mirrors the exploitation in Portugal. They should realize that about 45% of the population of Portugal is still illiterate and is controlled by an oligarchy which is linked up with western imperialism. We are against that system of government which perpetuates colonialism in Africa. Fifty percent of the Portuguese budget is spent on military activities in Africa; that money could be spent on education or social programs.

I also want to reiterate that our struggle is not a color issue between black and white. Our struggle is between the oppressor and the oppressed. We don’t view our struggle as being racist, we don’t see our fight as against white people although we are opposing white supremacy.

A question which I have been asked is what will happen to the struggle in Guinea Bissau now that Cabral is dead. One of the myths of the western world is that Africans are incapable of ruling themselves or making an orderly transition of government. They want to make you think that every time something happens, everything will fall apart. They assassinated Mondlane, but the fighters of FRELIMO have intensified their struggle in Mozambique. They killed Patrice Lumumba, but they did not stop progressive change in Africa. When Kwame Nkrumah died, the struggle in Africa did not stop. Certainly, the loss of Cabral will be felt deeply by the PAIGC, but whoever it is that they elect will carry on the struggle and it will gain the support of our people.

Angola will be free. Mozambique will be free. Guinea Bissau and Cape Verde will be free. Africa will be free (6). The end result will depend on what we all do.

QUESTION: An important question which we have been considering lately is the role of Cape Verdeans in the organization of the PAIGC. Would you please tell us how the people of Guinea Bissau view Cape Verdeans?

ANSWER: I think we should realize that Portugal went into Guinea Bissau and did many of the same things that she did on the Cape Verde islands. You will find, for instance, that those in the mainland speak the same type of Creole dialect that Cape Verdeans do. We don’t view ourselves as any different. We are all the same. I was there in the mainland and I was accepted. But if I go there as a Cape Verdean and a Portuguese at the same time, you can understand why I might not be accepted. You must remember that the Portuguese sent Cape Verdeans to her African colonies to serve as functionaries and to work as administrators over other Africans. They were led to believe that they were better than other Africans. These Cape Verdeans were, of course, only serving the interests of Portuguese colonialism. One of Amilcar Cabral’s important contributions was to deal with the problem of integrating Cape Verdeans with mainland Africans.

Some folks have also asked why we aren’t fighting on Cape Verde. The reason why we are fighting in Guinea Bissau first is that it was far more realistic strategically to initiate the struggle on the mainland. Amilcar Cabral’s position was that not even twins are born at the same time. We will take care of the birth of the first child and then the second. We would still like to bring about a negotiated settlement before the physical combat spreads into the Cape Verde islands, but if the situation demands it we would have no choice. There can be no alternative to the total independence of our people.

*My notes:

- Amilcar Cabral was born on September 12, 1924 in Bafata, Guinea-Bissau not 1925

- The sections in Bold explain some of the “resistance” to the liberation movement within the Cape Verdean community.

- This is a transcription of the interview with Mr Matteos. “Negro cachin” is probably “Negro ka genti”.

- “Oous-oous” probably refers to Cous Cous.

- The United Nations General Assembly approved, on November 2, 1973, a resolution that condemned the “illegal occupation by Portuguese military forces of certain sectors of the Republic of Guinea Bissau and acts of aggression committed by them against the people of the Republic”. One UN representative noted that an affirmative vote meant recognition of Guinea Bissau. There were seven (7) negative votes that day from Portugal, Brazil and Greece (both military dictatorships at the time), Spain (under the rule of Franco), South Africa (Apartheid), Britain … and the United States of America. During draft resolution debates, a Saudi delegate argued “Is that Statue of Liberty with its torch a sham?”.

- Angola became independent on November 11, 1975. Mozambique became independent on January 25, 1975. Guinea-Bissau became independent on September 24, 1973. Cabo Verde became Independent on July 5, 1975. Djibouti is the last African nation to gain its independence on June 27, 1977. Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (bordered by Morocco and Mauritania) is only partially recognized as of February 27, 1976.